Old-Time Orleans, Vol. 1, Issue 23

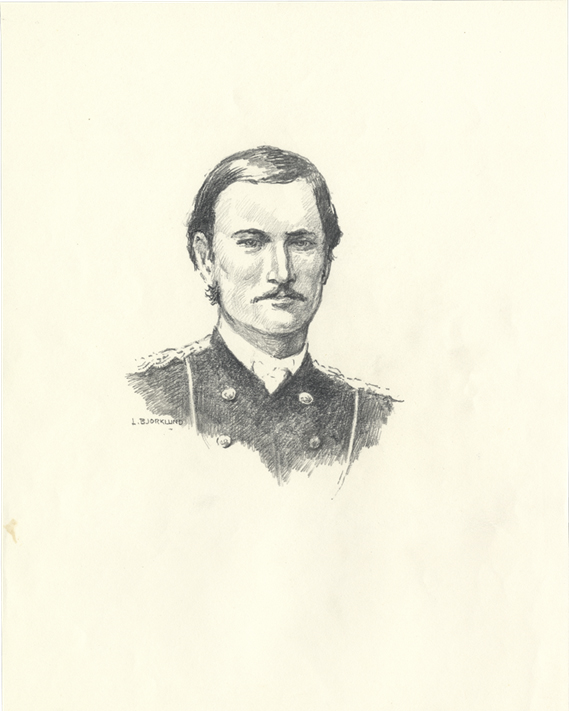

The son Shelby Harrington and Nancy Moore, Henry Moore Harrington was born at Albion on April 30, 1849. His maternal uncle, Charles Henry Moore, was a well respected entrepreneur and land speculator in Albion.

An astute and brilliant young man, Henry attended the Cleveland Institute at University Heights, Ohio where he graduated as valedictorian of his class. It was with these high honors that Harrington was awarded with an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy, an honor that he turned down in favor of a spot at the U.S. Military Academy in 1868.

Harrington’s time at West Point was completed in 1872, capped off by his marriage to Grace Berard, the daughter of a professor at the military academy. Shortly thereafter, Harrington was assigned as a lieutenant with the 7th U.S. Cavalry and stationed in the Carolinas for training during the winter and spring of 1872/1873. These training exercises were to prepare Harrington and the other men for service in the west.

l-r: James Calhoun, Margaret Custer Calhoun, Grace Berard Harrington, Henry Harrington – Harrington was said to have been a member of George Custer’s “inner-circle” and here he is photographed with Custer’s sister and brother-in-law.

Stationed at Ft. Lincoln and Ft. Rice in the Dakota Territory, Harrington was in service alongside George Armstrong Custer during the Yellowstone Expedition in 1873 and the Black Hills Expedition in 1874, the latter discovering gold in the hills of the Dakotas.

It was during the Great Sioux War of 1876 that Lt. Harrington would distinguish himself as one of the bravest men ever encountered by the Sioux Nation. On June 25th, Custer divided his 7th Cavalry into three columns. Due to a shortage of officers, Harrington was assigned to Company C where he would serve alongside Capt. Thomas Custer, the younger brother of George.

Outnumbered upwards of 20 to 1, Custer’s men crossed the Little Big Horn River and led a charge against the northern end of the Native American village. Against insurmountable odds, the men made their advance on the village and were completely annihilated.

It was during Custer’s overly glorified “Last Stand” that Harrington was said to have escaped on his “unique, large sorrel.” Breaking through the encirclement of Native American warriors, he was pursued by seven men. Based on accounts of the engagement, remains believed to be those of Harrington were found nearly eight miles away from the battlefield.

Harrington’s remains were never found or identified following the battle. His wife searched for three years in the hopes of finding his remains but returned home empty-handed.

In 2006, forensic scientists with the Smithsonian Institute identified remains within the museum’s anthropological collection as those of Henry Moore Harrington. Dr. Robert Shufeldt had retrieved the skull in 1877 from a location some distance from the battlefield, leading to misidentification.

Harrington was 27 years old at the time of his death, leaving a wife and two children to mourn his passing. The family erected a cenotaph in his memory at Coldwater, Michigan.

Henry Harrington was the nephew of Albion businessman Charles H. Moore (vol. 2, issue 2).