Volume 3, Issue 43

The trial of George Wilson, accused of murdering his wife Alice in 1887, remains one of the most infamous stories in Orleans County. His trial and execution is a tale filled with speculation and accusation, while the later story of District Attorney William P. L. Stafford is shrouded in spite and hatred following his upsetting defeat in the 1895 election for County Judge. Despite its popularity, much of the story exists as hyperbole and conjecture concerning Stafford’s motives following his embarrassing loss.

I was contacted by Gerard Morrisey following my article featuring John Newton Proctor and kindly reminded that the property, which was so scandalously sold to the Catholics by William Stafford, was in fact sold by his wife Clara. It is important to trace the lineage of the property itself to better understand the situation in which the Staffords were faced with in 1896. It is also important to note that in 1848, New York passed the Married Women’s Property Act that gave married women the right to own real and personal property that was not “subject to the disposal of her husband.”

John Newton Proctor entered the employ of William Gere upon his arrival in Albion and shortly after married Gere’s daughter, Orcelia. Gere and Proctor’s partnership was dissolved upon the death of Gere in 1865 and the subsequent death of Gere’s son Isaac in 1866. The Proctor’s lived on the Gere parcel at the intersection of West Park and Main Streets until Orcelia’s death on March 7, 1888. Upon her death, Mrs. Proctor bequeathed to her husband “the House [and] premises situate[d] in Albion aforesaid in which I now reside [and] being the same premises which my parents lived at the time of their death;” a clear indicator of who owned the property.

The parcel fell under the ownership of Mr. Proctor for a very short period of time, as his untimely death on February 11, 1889 transferred the property again. Proctor clearly expected his wife to predecease him as his will left everything to his wife with no mention of children. The result was a transfer of all property, real and personal, to his daughter Clara Stafford, which in addition to the beautiful and stately brick residence also included a commercial parcel in downtown Albion and other parcels throughout the area.

The traditional narrative revolving around the parish of St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church says that ex-District Attorney Stafford, a “disgruntled Baptist,” sold his property to the congregation. In fact, it was Clara Stafford who sold the parcel to the Catholics, as it was not her husband’s property to sell. In 1895, William Perry Lucian Stafford made a daring charge at the position of County Judge, challenging Isaac S. Signor to a battle for the Republican nomination. When Stafford was nominated over Signor, the Republicans shifted their attention to attacking the credibility of Stafford as a candidate and allegedly encouraging many local voters to defect to the Democrats. Ben S. Dean of Jamestown sent a lengthy letter to the editor in early October of 1895 stating locals were spreading stories that “Mr. Stafford was buying beer for the Polanders” and slinging other outrageous accusations. In closing he wrote, “it is not good politics to have a Democratic County Judge in office in a Presidential year.”

Later stories suggested that Republican voters were “tricked” at the caucuses, which resulted in W. Crawford Ramsdale’s 279 vote victory over Stafford in the election. Stafford later told newspaper editors that Irving M. Thompson of Albion was behind his defeat, becoming defiant after his nomination, and encouraging other Republicans like Edwin Wage, R. Titus Coann, Isaac Signor, and others to follow suit, throwing “all the ice water he could on the Republican ticket.” It was clear that Stafford’s distaste for the Republicans was more of an issue than lack of support from the Baptists.

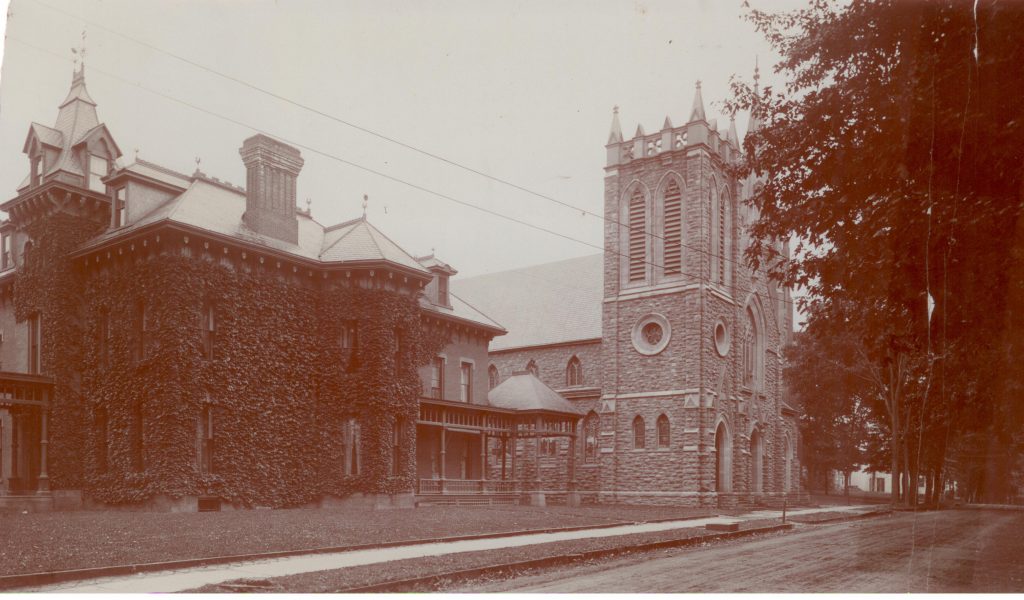

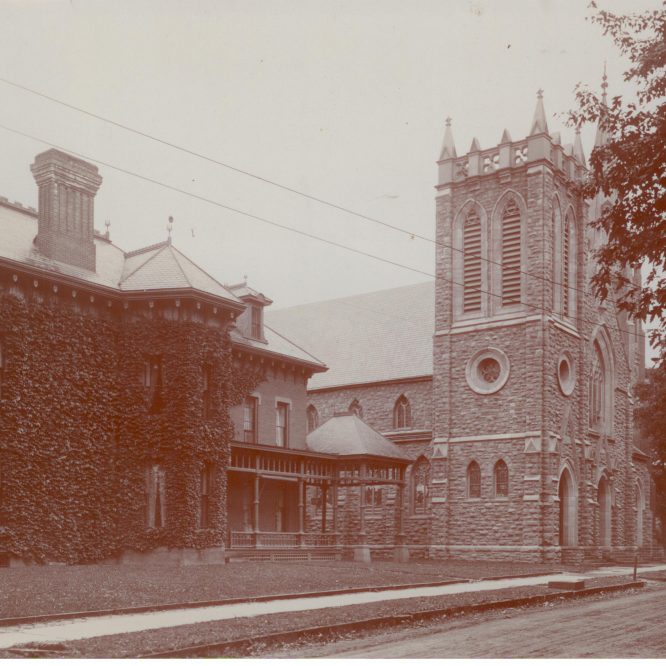

Local lore claims that Stafford sold his house to the Catholics, uprooted his family (including his deceased children), and relocated to California. The February 18, 1896 indenture notes that Clara Stafford was already living in Los Angeles at the time of the transfer. The parcel, sold at $9,000 (or approximately $262,000 today) included the “brick dwelling house, brick barn, and brick tenant house.” Mrs. Stafford reserved use of the dwelling house until May 1, 1896 and the use of the attic for “the storage of her personal effects” until April 1, 1897; the transfer was signed by her, not Mr. Stafford, and makes no mention of her husband.

The other piece of local lore involves the anecdote that Mr. Stafford required that the Catholics build their church as close to the street as possible, as to block the view of the Baptist edifice. This is likely exaggerated as no written claim to this exists, however, the local papers published a notation that highlighted the Baptist’s displeasure with the sale. The writer notes that the parcel of land was sold by Mrs. W. P. L. Stafford, but the agreement could be broken at the cost of $500. The Baptists were concerned that the “chanting, responsive reading, etc. of the Catholic service [would] cause great annoyance to their own services during the summer months when the windows…would be apt to be open.”

Although it was long believed that Stafford’s role in the prosecution and execution of George Wilson led, in part, to his defeat in 1895, his challenging of conventional party politics was viewed as the likely culprit. After his departure from Albion, he remained connected to the area through family and friends, visiting on occasion until his death on September 17, 1919. The story of Stafford’s spiteful sale of his house to the Catholics may not be entirely true, but it remains an intriguing part of Albion’s history. After all, legends are often rooted in truth.