Volume 3, Issue 45

No building served a more important function to society on the frontier of Western New York than the barn. This structure was essential to the operation of infant communities across the United States and we find numerous examples throughout local history of the significance of the barn. In Barre, the First Congregational Church (later the First Presbyterian Church of Albion) was organized in the barn of Joseph Hart and the barn of Ezra Spicer at Kendall was the focal point of Methodist revivals during the Second Great Awakening. The first town meeting for Murray was held in the barn of Johnson Bedell outside of Brockport and the small village of Hulberton utilized a barn south of the Erie Canal for a school until a framed building could be constructed in 1828.

Barn raising, or “raising bee,” was an important piece of rural life in the 18th century. At a time when cash was nearly non-existent and rarely exchanged between pioneers, this form of reciprocal labor involved the collection of capital in the form of favors that ensured the success of small, self-sustaining farmers. Throughout the 19th century, during times when neighbors were few and far between, the opportunity to participate in a barn raising was a prime occasion for families to engage in community building and fellowship. In the years of early settlement in Orleans County, in the absence of an abundance of able-bodied men, farmers relied upon volunteers from outside of the region; Seymour Murdock’s barn raising in Ridgeway took place under the assistance of U.S. troops serving with Gen. George Izard during the War of 1812.

Preparatory work was required before a barn raising could take place. The farmer would start by seeking out the assistance of a contractor or builder who could draft plans for the barn, providing dimensions for the proposed structure. Then the necessary building materials were acquired, the ground leveled, the foundation constructed, and the timbers assembled to form a frame. Clarence Steele, in his 1978 oral history, recalled the process for raising the framed walls. Men used large pike poles to push and hold up the frames while a carpenter or joiner scaled the walls to fasten them together; the ends were put up first followed by the sides. Men from across the town were invited to participate in this community building activity. The more experienced men, those who participated in numerous barn raisings, were expected to take on leadership roles in the process.

The construction of barns was a community event, involving women and children in addition to men. While the men completed the work necessary to assemble the barn’s framework, women were working diligently to prepare food for the workers. The significance of this role was reflected in a Holley Standard article published in 1889, noting that men participating in a recent barn raising at Clarendon received no food or drink, nor even a thank you, for their hard work; they were far from happy with this outcome.

Regardless of their “reward” for participating in the project, an invitation to participate in a barn raising was a privilege. The Holley Standard noted in 1899 that “a number from [Holley] were fortunate enough to get an invitation to the barn raising on the Salisbury farm this week.” In 1892, William Clark invited over 100 men to assist with his barn raising at Clarendon and just over two decades later, a barn raising at the farm of Mr. Kelley at East Albion attracted around 50 men. The decrease in the number of men utilized in raising Mr. Kelley’s barn is, in part, an indicator of the phasing out of this age-old tradition.

Of course, raising large timbers to construct a barn was far from a safe task. In July of 1880, David Hills of Oak Orchard was killed by falling timbers while raising a barn north of Medina. Several decades later, Fred Fulton was injured in a similar fashion on the farm of Varnum Ludington. Mr. Fulton’s attempt to sue the Ludingtons in 1911 likely demonstrates a violation of the unspoken code of volunteer labor shared between neighbors.

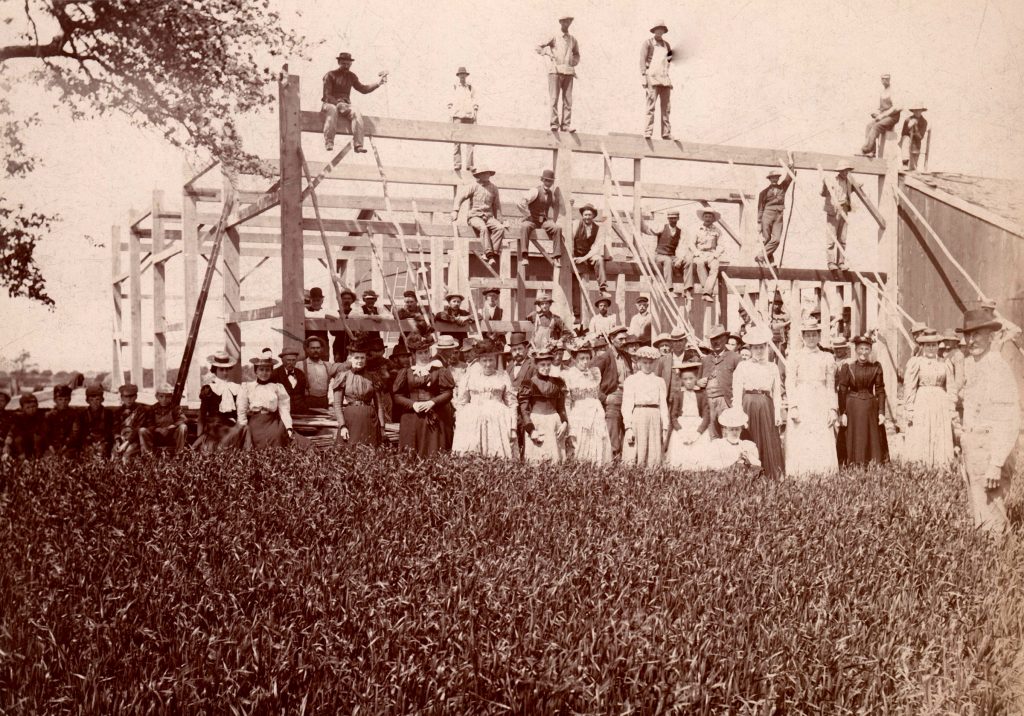

This photograph, simply marked as “Murphy’s Barn Raising,” illustrates the role that the barn raising played in local society. Standing along the top beams are carpenters, wearing aprons and holding hammers necessary to join the framed sections. The pike poles used to hoist the framework are still propped up along the walls. One will notice the variety of outfits present for this event as the women are dressed in fine clothing, with some men standing close by in suits. The men who came to work are differentiated by their lack of jackets or presence of overalls and suspenders. Also noticeable are the six young men lined up on the left, dressed to help with the project. Without any additional identifying information, the man standing on the right is likely the farmer or the contractor supervising the construction.