Volume 3, Issue 47

Following the passing of New York’s amendment that extended voting rights to women in 1917, the subsequent election involving the question of whether Albion would remain a “wet” or “dry” town was decided by the female vote. Although the vote was later deemed invalid, the local temperance organizations mobilized a sufficient number of new voters to end the sale of alcohol in Orleans County, even if only for a brief moment.

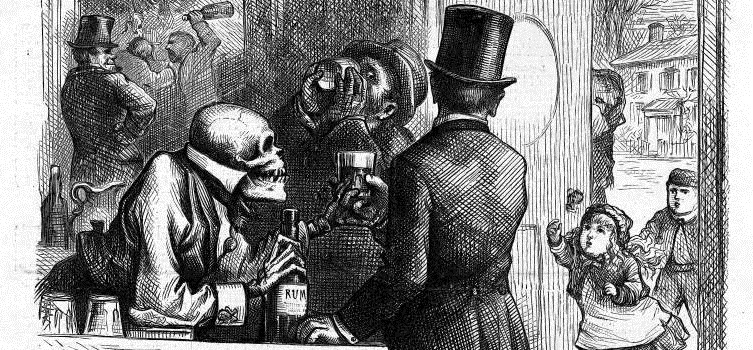

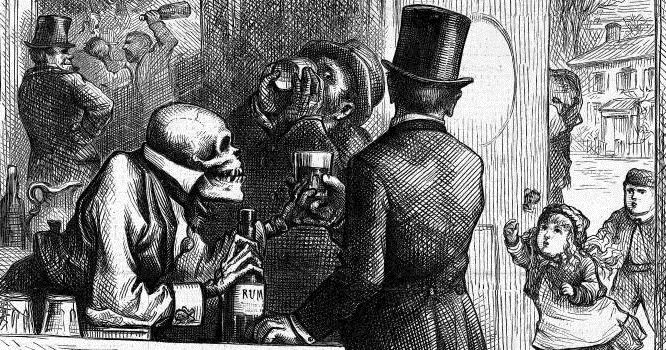

This Thomas Nast cartoon appeared in Harper’s Weekly on March 21, 1874 and depicted the debaucheries commonly associated with the saloon. A man of the middle-class accepts a drink of rum from the bartender who is depicted as death. The man’s young daughter pleads for her father to come home while his son looks on with concern and a man lays to the right, passed out in the corner of the room. In the distance is the man’s home and his wife, dressed in black, weeps behind her children. On the floor sits a hat, a broken bottle, a brick, and a revolver, all symbolic of the violence commonly associated with alcohol consumption. In the background a man watches through a doorway as men brawl with one another, one man ready to strike another in the head with a bottle.

Local temperance movements grew out of the reform activity of the early 19th century commonly associated with the Second Great Awakening that flooded through Western New York. Members of the upper and middle classes went to battle against the intemperate behavior of the lower, wage-earning and unskilled laborers who flooded the region to toil along the canal and in the quarries. In Orleans County, the early arrival of Irish and German immigrants and later the Polish and Italians bred contempt against groups of people who were perceived a prone to consuming alcohol.

In the early 1870s, Albion had three active temperance organizations, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Albion Temperance League, and Drunkard’s Reform Association. The Albion Temperance League organized around 1874, holding meetings at the Free Methodist Church, where Edwin R. Reynolds was selected as the organization’s permanent president. Other prominent local residents joined the ranks as officers, including John G. Sawyer, Arad Thomas, Joseph Cornell, Ezra T. Coan, and Free Methodist minister Alanson K. Bacon. In the latter half of the 1870s, Medina boasted 6 active temperance societies with 840 members, nearly 1/5 of the village’s total population.

Drunkards posed concerns for local residents, unable to work, engaging in violence, and abandoning wives and children. On July 30, 1882, Isaac Harrington of Medina was riding a train to Albion when the conductor removed him from the car on account of his intoxication. Harrington passed out on the tracks and was run over by a passing locomotive shortly after. A month later, John Mack of Kendall traveled to Albion to catch a glimpse of Jumbo the elephant’s visit to the area. Instead of focusing on the visit, he fancied a nip of the bottle, fell off a dock, and drowned in the canal.

Excessive drinking had the potential to affect all members of the family, not just the individual. In 1879, Albion papers reported a nine-year-old boy who was wandering drunk through the village streets, though there was no further report of the young man’s parents. Medina reported a similar occurrence the previous year when a 13-year-old boy was found drunk with whiskey in his coat pocket. Three years later, Nicholas Gavin, a farmer from Albion, was enjoying a few drinks at a saloon downtown before venturing home for the evening. Drunk and befuddled, he drove his buggy over the Main Street bridge, turned onto the tow-path and traveled a short distance to the east before steering his horse into the canal. His body was discovered beneath the frozen water the following morning; he left a wife and five children to mourn his death.

Perhaps one of the most shocking stories of the late 19th century was the case of James O’Connell of Fletcher Chapel. The violence-prone farmer went on a week-long binge, much to the disappointment of his wife. On January 16, 1896 he told his wife he would visit the priest at Medina to “sign the pledge” and give up drinking. Instead, he visited a gun store in Medina and purchased a .22 revolver, returned home, and shot his wife in the head. Although she survived the incident, she lived the remainder of her life with the bullet in her skull and O’Connell spent eight years in Auburn Prison for the deed.