Vol. 4, No. 18

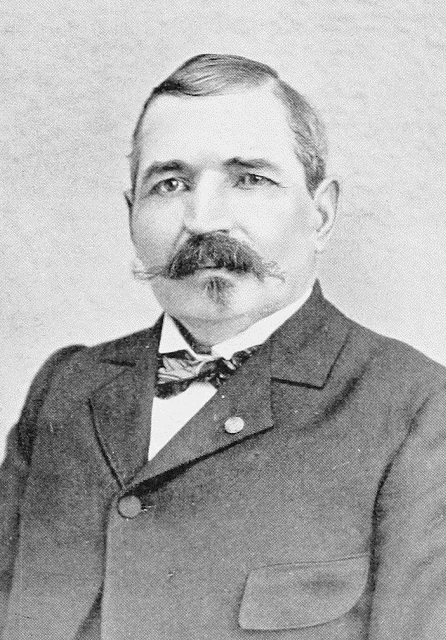

As I prepared last week’s article about Asa Hill of the 28th New York Infantry and his beautiful monument situated at Millville Cemetery on East Shelby Road, I stumbled upon an image of another soldier from the same unit. Several years ago I encountered the story of William Collins but was unable to locate an image of him. As the 153rd anniversary of the capture and death of John Wilkes Booth passed on April 26th, I thought perhaps it would be worthwhile to recall this particular story.

William Collins was born September 28, 1843 to Michael and Susan Collins of Albion. His father was an Irish immigrant who worked as a day laborer in the village, raising a rather large family in the vicinity. Little is known about William’s early life, but shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War in April of 1861, the 17 year old enlisted and as was mustered into service on May 22, 1861 with Company G of the 28th New York Infantry, one of the first units raised in Orleans County.

Collins quickly progressed through the ranks, receiving a promotion to corporal on February 22, 1862 before his capture at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862 – the same engagement that resulted in the amputation of Asa Hill’s right leg. He was paroled, promoted to sergeant on December 7, 1862, and according to several accounts, was once again captured at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863 before being mustered out on June 2, 1863.

Falling into enemy hands on two separate occasions within a period of nine months might suggest that Collins was far from a lucky man. Yet this did not prevent him from reenlisting on June 20, 1863, this time with Company K of the 16th New York Cavalry. While serving with his unit at Leesburg on April 20, 1864, he was one of two enlisted men wounded. To add to his misfortune, just two months later on June 24, 1864, he was captured at Centreville, Virginia and sent to Andersonville Prison where he spent approximately seven months before his parole.

His obituary notice, following his death on March 17, 1904, notes an interesting tidbit of information surrounding the end of his service in the Union army. After he was paroled from Andersonville, he returned home to Orleans County where he spent several months with a severe illness. The terrible conditions experienced by Union prisoners of war in Georgia would have proved detrimental to the healthiest of soldiers and it is presumed that these conditions were the cause of his extended sickness. Upon his recovery, he was sent to Washington, D.C. where he rejoined the 16th N.Y. Cavalry. In the weeks following his return, the assassination of President Lincoln on April 14th/15th created quite the commotion, initiating a manhunt for John Wilkes Booth and David Herold.

Although there appears to be little evidence to confirm his participation, William Collins was said to have been one of 25 men who volunteered as part of a detachment of the 16th N.Y. Cavalry to pursue Lincoln’s assassin. On April 26, 1865, the unit surrounded a barn on the Garrett farm south of Port Royal, Virginia where Booth and Herold were believed to be hiding. When Booth refused to surrender, the barn was set ablaze by lighting straw with a match in an effort to coax the killer out. Sgt. Boston Corbett claimed that Booth raised his carbine, prompting him to shoot Booth in the back of the head with his Colt revolver; the assassin was dead two hours later.

In the years following the war, local papers noted that Collins received $1,500 (nearly $25,000 today) for his participation with the detachment that captured Booth. Starting in the late 1880s, he assembled a lecture on his exploits with the 16th N.Y. Cavalry, highlighting his participation in the pursuit and capture of Lincoln’s killer. He spent the remainder of his life in Albion, building a house on McClelland Street in 1893 and working as a pension agent. In 1904 he suffered a stroke and was sent to the Orleans County Alms House to recover. As his condition worsened, he was transferred to the Soldiers’ Home at Bath, NY before spending the remainder of his life at the Willard Insane Asylum. His body was returned to Albion for internment at Mount Albion Cemetery.