Vol. 4, No. 32

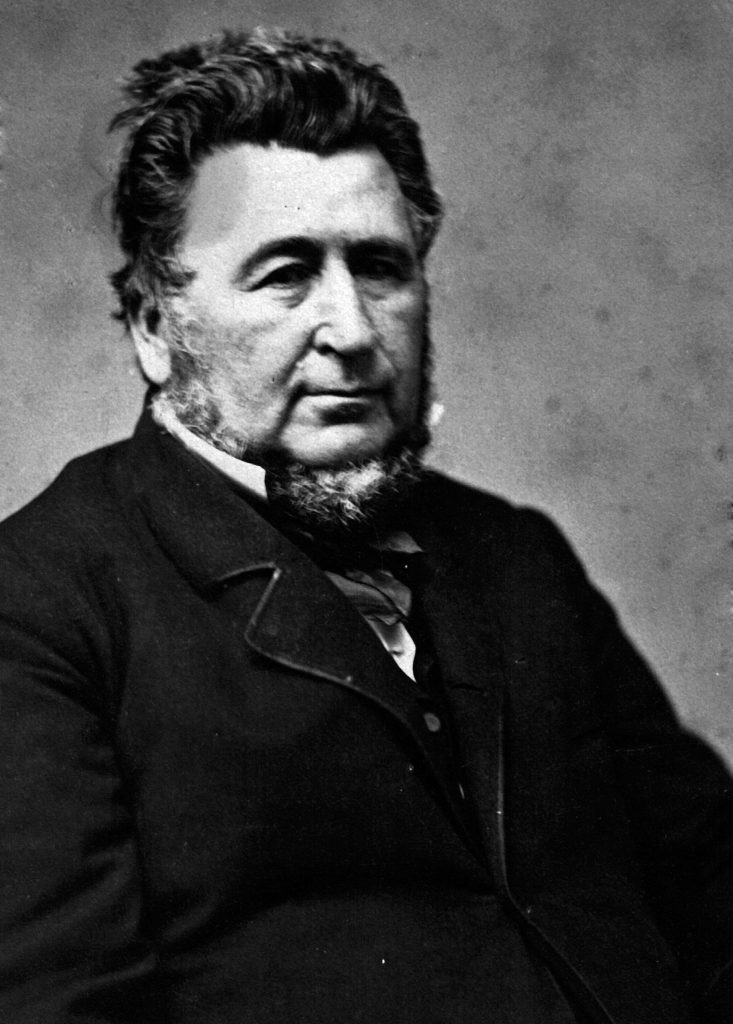

As tours of Mt. Albion Cemetery continue every Sunday through the month of August, I noticed a particular headstone that is frequently passed over each year. Progressing up the winding hills towards the Soldiers & Sailors Monument at the peak of the cemetery is a moderately-sized, dark greyish-blue stone that reads “Father – Benjamin L. Bessac, 1807 – 1871.” The stone is rather reserved in comparison to the larger, ostentatious obelisks and monuments that stand around it. Benjamin Lisk Bessac, the feature of this article, was one of the most notable attorneys in Orleans County who mentored the area’s premier lawyers.

Born on March 12, 1807 at New Baltimore, New York, Bessac’s mother died when he was just 12 days old leaving his father a widower with an infant child. Some reports differ as to who exactly cared for the child in infancy, some suggesting his grandparents while others suggest an aunt who lived in the vicinity. According to family stories, Benjamin Bessac was the grandson of Jean Guillaume (John William) Bessac, an assistant surgeon attached to the staff of Count de Rochambeau during the American Revolution.

Bessac was educated in the common schools while living with his grandparents. During this time, his father packed up his business interests in Chenango County and started west for Ohio. Upon reaching Ransom’s Grove in Erie County, now the town of Clarence, he was stopped by a frightful snow storm and quickly opened a blacksmith shop with the few tools he carried and a small reserve of iron. In the summer of 1822, having established himself on 160 acres of land near the Great Rapids along the Tonawanda Creek, Lewis wrote to this son and encouraged him to come to the Western New York frontier to live on this growing farm.

After three years of living the pioneer life, Benjamin determined that his life was better suited in the pursuit of knowledge than battling the physical demands of the frontier. On October 2, 1825, Bessac walked to Lockport where he boarded a packet boat bound for Albany. It was during this time that he passed through the fledgling settlement of “Newport,” which he described as “…that low, muddy, and as I thought unsightly young village” and proclaimed it to be “…a queer place on which to build a town.”

Upon his return to Albany, he commenced teaching over the winter of 1826 to which he wrote, “My education was not such as the district schools of this day afford. My mind had been somewhat improved by reading in a desultory and aimless manner.” In the spring of that year, he was hired to work on a farm for $9.00 per month outside of Albany and once again commenced teaching school the following winter. In 1827, Bessac entered the Greenville Academy and then prepared to enter the sophomore class at Union College; instead, his friends secured him a job as a store clerk in New York City.

For a short period of time, Bessac relocated to Mobile, Alabama where his wife established the Mobile Female Seminary while he worked as a clerk in a U.S. Bank. Upon the passing of his wife, he transferred the seminary to another individual and returned to New York. He studied law in Cairo, New York under Amasa Mattoon and later Hiram Gardiner in Lockport before returning to that “low, muddy…and unsightly young village” now known as Albion. After settling in Albion, a young Sanford E. Church commenced reading law in his office and became Bessac’s first partner. Over the years, many up and coming attorneys read law in his office including his last partner, George Bullard.

In a few closing notes, Bessac owned a large portion of land on the east side of Main Street stretching from the Erie Canal to the Gaines town line. After constructing a house near what is now Linwood Avenue, at 231 North Main Street, it was determined that an access road should be added to the property just north of the Canal. According to Village of Albion historian Neil Johnson, Bessac ran the street straight eastward until reaching a swampy area along the canal, forcing the road to turn slightly northward. The roadway was opened through to the vicinity of Brown Road where it terminated. Caroline Street, as we know it, was named after Bessac’s second wife, Caroline Baker.