Vol. 4, No. 37

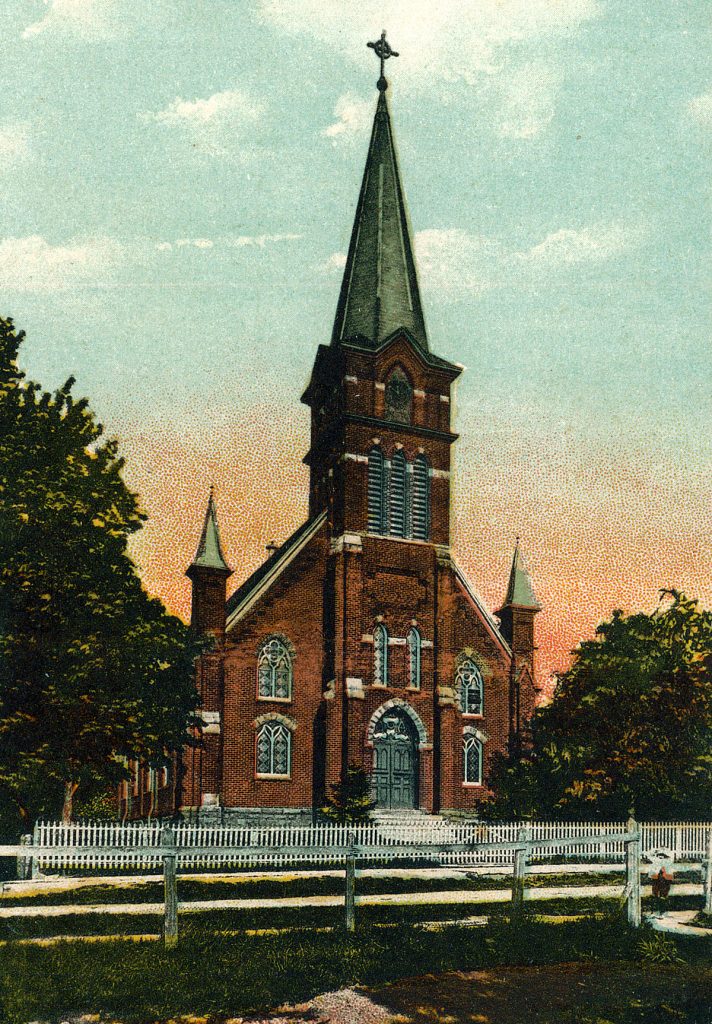

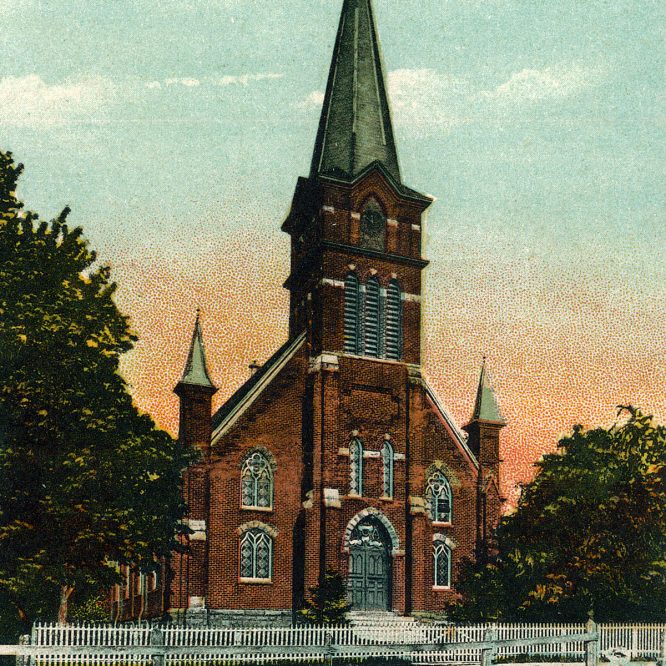

Some of the best local history stories are those that are rediscovered and built upon by each historian. While organizing a collection of newspaper clippings, I stumbled upon a particular story that holds a special place in my heart. “Why the Bell Rings,” vol. XXIX no. 1 of Bethinking of Old Orleans authored by Bill Lattin recounts a story relating to St. Mary’s Assumption Church in Albion. His discovery of a newspaper clipping within a scrapbook led him to write a short piece about the Angelus Bell.

As a young boy, I can recall the frequent tolling of the bell at our parish on Brown Street. In my naiveté I thought for sure that the evening bell was a simple curfew reminder, but over the years I have developed an appreciation for the deeper meaning of the scheduled bell tolling. Even though the bells now stand silent, except for the Sunday call to service, the story is an important one centered on tradition and faith.

In 1907, complaints arose locally about the church bell at the “Polish colony.” As observed in the Orleans Republican, it is clear that the publisher of the Orleans American took issue with the frequent ringing of the bell. The November 20, 1907 issue of the paper published an article entitled “The Angelus Bell; A beautiful custom, general in foreign lands, observed by the Poles,” which opened with “Will the Orleans American be good enough to tell its correspondent to stop chattering against the ringing of the church bells?”

This must be the same situation from which Lattin extracted his information, quoting another newspaper story in which a local Polish resident was asked about the frequent ringing. “At the hour of work it rings to remind them that God has given them the strength to labor. When it sounds at noon, the Poles are again reminded of the Giver of temporal blessings, and at night it calls for expressions of thankfulness for what God has done for the people throughout the day,” one resident stated, “In the old country at home the church bells are always rung in this way.”

The particular situation called attention to the Angelus Bell, sometimes referred to as the Ave Bell. Catholic tradition called for the ringing of the church bell three times throughout the day, typically at 6 o’clock in the morning, noon, and 6 o’clock in the evening. At those times, the ring consisted of a triple stroke repeated three times with a short pause in between each set; many churches opted to follow the three sets of triple strokes with nine additional strokes. The term Angelus Bell is derived from angelus domini, the phrase preceding the archangel Gabriel’s greeting to the Virgin Mary. According to Luke, Gabriel would reveal to Mary that she would conceive a child to be born the Son of God (Luke 1:26-38).

The origin of the practice is often attributed to either Pope John XXII or Urban II, while the triple recitation of the Hail Mary is attributed to Louis XI of France during the 15th century. When the bell rang, the faithful would cease work and pray the Angelus, beginning with “The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary. And she conceived by the Holy Spirit,” followed by a Hail Mary. Each versicle was followed by a Hail Mary with three recited in total. Individuals could recite these prayers alone or as part of a group with leader and response parts. Although these prayers often marked the start and end of a day, their purpose extended beyond the temporal. One can imagine those laboring in the fields and quarries, hearing the bell toll and gathering together to recite the Angelus.

Jean-Francois Millet’s painting entitled L’Angelus, or “The Angelus,” depicts two peasants standing in a potato field having ceased their work to pray. In the distant background is a village with a church steeple protruding into the horizon as a symbol of the Angelus. Asked to reflect upon this particular piece of art, Millet said, “The idea for The Angelus came to me because I remember that my grandmother, hearing the church bell ringing while we were working in the fields, always made us stop work to say the Angelus prayer for the poor departed.” Millet’s work is a reflection of the simplicity of peasant life so dependent upon the rhythms of life and the Catholic faith.