Vol. 4, No. 52

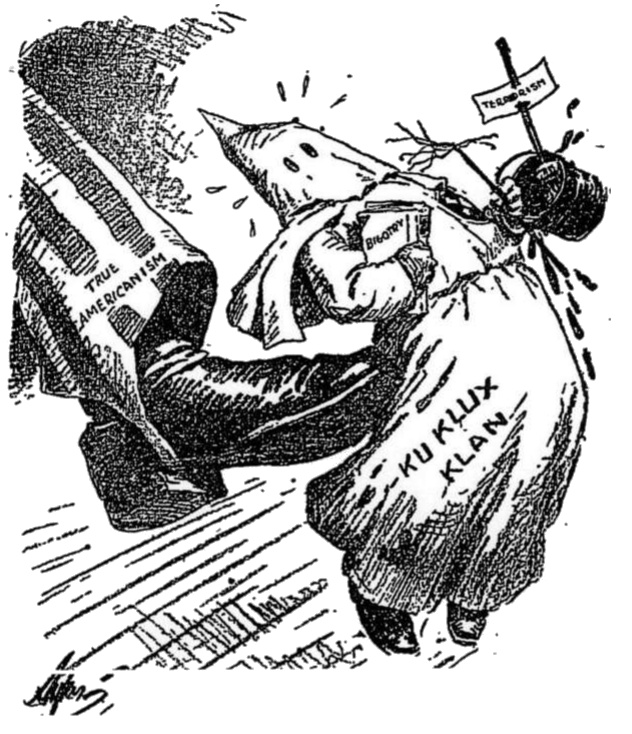

An article published last weekend in the Orleans Hub entitled “KKK meeting in Albion in 1925 included parade with 900 Klansmen” was met with mixed reactions and controversy, labeled as “glorifying” the organization or what it stood for. It seems that a follow-up piece is necessary for clarification.

In 1992, C.W. Lattin wrote an article on the same subject entitled “Ku Klux Klan Hold Picnic at Fairgrounds Labor Day,” taken from the headline that appeared in the Orleans Republican newspaper in 1925. Ray Cianfrini, an attorney in Oakfield and retired Genesee County legislator has also authored pieces on the same subject, presenting on the activities of the Ku Klux Klan in Genesee and Orleans counties. The study of these disturbing pieces of history demonstrates that all history is local and small, rural communities were not exempt from the type of racial, ethnic, social, and political turmoil experienced in other regions of the United States. More importantly, it calls attention to the fact that this particular photograph, captured 93 years ago, is not exclusively “historic.”

Albion native Rufus Brown Bullock experienced the racial and political pressures of the Ku Klux Klan during his tenure as Governor of Georgia. Bullock became one of the first Republican governors elected during Reconstruction in 1868, signaling an end to federal military presence in the state. His pro-African American policies created contention in his administration, leading to ridicule, scandal, and accusations of embezzlement and theft of state funds. It was under the pressure of the Ku Klux Klan that he resigned and returned to Orleans County in 1871. Succeeded by Benjamin Conley for the remaining two months of his term, Bullock was the last Republican elected as Governor of Georgia until Sonny Perdue in 2003.

When readers see the name Ku Klux Klan, minds immediately turn to race-based violence, lynching, and cross burning. Such behavior was typical of the KKK in the south, but not typical of Upstate New York activity in the 1920s and 1930s. The Second Klan, established in 1915 outside of Atlanta, Georgia, sought to combat perceived threats to morality (divorce, adultery, and alcoholism) and perceived threats to Protestant Christian ideology. Northern targets of the Ku Klux Klan tended to be Catholics, Jews, immigrants, and those perceived to be living an immoral life; all of these populations, in addition to African Americans, lived in Orleans County.

It is for this reason that the Ku Klux Klan became active in Orleans and Genesee counties during the 1920s. Growing numbers of Polish and Italian immigrants created a perceived triple threat to the Klan; they were Catholic, immigrants, and stereotypically perceived as prone to alcohol consumption. At the height of Prohibition, some groups were known locally for their production of bootleg liquor and consumption of alcohol in speakeasies and secret bars. Similarly, the Irish settled in Orleans County over 50 years earlier, but quickly became targets of anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments. (Additional information about Temperance, see Overlooked Orleans v. 3, no. 47: Additional information about Local Immigration, see Overlooked Orleans v. 3, no. 26: Additional information about Prohibition-era Raids in Orleans County, see Overlooked Orleans v. 2, no. 18 and v. 3, no. 22)

Lattin’s article indicates that the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Orleans County was not unknown, but the exact extent of that presence during a very small window of time in the mid-1920s is cloudy. According to Roland Fryer and Steven Levitt, the membership of the Ku Klux Klan in the United States peaked in 1924 in the range of 1.5 million to 4 million, or approximately 4%-15% of the eligible population.

Dr. Shawn Lay, a scholar on the Klan in Western New York, notes that not all men who joined did so based on racism, instead “many men [joined] simply out of curiosity or because they did not want to be left out of what appeared to be an up-and-coming organization. An individual’s decision to join the Invisible Empire could not always be solely credited to racial and religious intolerance.” To many, the organization appeared as a fraternal, nativist, and patriotic one, fighting to uphold Prohibition.

The article describing the parade that took place on Labor Day of 1925 notes that village officials, who required that all participants march without hoods or masks to cover their faces, opposed the parade. This was likely the reason why no members from the central or eastern townships participated in the event; the fear that fellow neighbors would know of their participation with the organization. The article also notes that Chester Harding, the president of the Orleans County Agricultural Society, was responsible for renting the fairgrounds to the Klan for $100 resulting in “considerable criticism” from members of the community. It was understood locally that the Agricultural Society was experiencing financial troubles, making the decision to rent the grounds quite difficult.

Dr. Lay’s study of the Ku Klux Klan in Buffalo suggests that activity was not outwardly violent against African Americans and immigrants, instead demonstrating efforts by the organization to exist within established political and power structures. It is no surprise then that during the 1920s, the United States witnessed the passing of the strictest immigration laws in the history of the United States. This does not mean that zero instances of violence occurred in Western New York, instead suggesting that the Klan sought to oppress these specific marginal groups through legislation and policy.

The Ku Klux Klan was met with major opposition in Western New York, particularly in Buffalo, where a membership list was stolen and published in 1924. Listing members from across Erie, Niagara, Genesee, and Orleans counties, the pamphlet sought to vindicate those wrongfully accused of participating with the organization. Ray Cianfrini described a similar situation when members of the Klan pursued a Labor Day parade in Batavia that same year. The local newspaper threatened to publish a list of local members should the organization hold their parade; the KKK called the newspaper’s bluff and the list was published soon after.

In one final closing note, an article entitled “Sheriff’s Tenure Marred by Local KKK Activity,” (Overlooked Orleans, v. 2, no. 48) elaborates on the political support received by Ross Hollenbeck for Orleans County Sheriff in 1924. Members of the KKK in Lyndonville sent a letter to the Orleans County Board of Supervisors accusing Deputy Sheriff Jerry Butts of attending their meetings with the intention of causing trouble; Sheriff Horace Kelsey relieved Butts of his duties soon after. It is no surprise then that the Ku Klux Klan opposed a candidate for Sheriff previously involved with efforts to disrupt their activity.

The focus of these stories is not to glorify the Ku Klux Klan, but to call attention to the extent of racial, ethnic, religious, and political tensions experienced within a small community. Residents felt the fear and turmoil created by the presence of local Klan members and stories of cross burnings on the properties of local politicians, immigrants, and Catholics still circulate today.

There is much more to learn about the difficult stories of our past than simply preventing the same mistakes, history provides an opportunity to better understand the issues of the present.