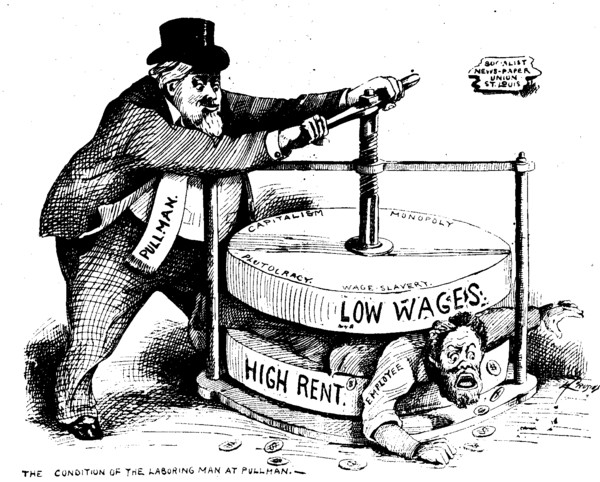

“The Condition of the Laboring Man at Pullman” Political Cartoon, circa 1894

Vol. 5, No. 9

March 3rd marks the 188th birthday of George Mortimer Pullman, born in 1831 to James Lewis and Emily Caroline Minton Pullman. In 1845, George had reached the age of 14 and received a sufficient level of education in the common schools to enter the workforce. It was around this time that James Pullman brought his family to Albion, “where he became widely known as a useful and upright citizen,” according to W. B. Cook.

The untimely death of James in 1853 forced George to care for his mother and younger siblings. Working as a cabinetmaker, Pullman was best known locally for building furniture in a business that would eventually transition through the hands of George Ough, to the partnership of Reynolds & Flintham, to J. B. Merrill, and eventually transition to the business formerly known as Merrill-Grinnell Funeral Home. It was during an 1853 construction project along the Canal that Pullman developed a reputation for himself as a master contractor. Using a tool developed by his father, Pullman was able to move several large buildings to make way for the widening of the canal prism. Two years later he and Charles H. Moore traveled to Chicago where they performed similar work, raising buildings to prevent flooding.

In the late 1850s, Pullman entered into a partnership with Ben Field, who became one of the primary financiers of the sleeper car experiment. Field would eventually sell out his interests to Pullman in order to pursue politics and, of course, the latter “made out like a bandit.”

The story of George Pullman is often romanticized, telling the story of a great inventor with a brilliant mind for business. Instead, we should view Pullman’s career in a critical light. One defined by the treatment of his employees.

This political cartoon, entitled “The Condition of the Laboring Man at Pullman,” provides insight into the public’s perception of Pullman. In this cartoon, an employee is pressed between the weights of high rent and low wages; the upper press reads, “Capitalism, Monopoly, Plutocracy, Wage Slavery.” A hefty George Pullman is operating the t-screw on the press, his weight indicative of an exorbitant lifestyle fueled by wealth and greed.

In 1880, Pullman purchased 4,000 acres of land at Lake Calumet and employed Solon Spencer Beman to design a factory for manufacturing sleeper cars. It was Pullman’s idea to construct a company town for his employees, equipped with housing, stores, churches, and entertainment venues. The utopian-like community was void of vices that Pullman perceived to damage society, including saloons, in an effort to increase worker loyalty.

Unfortunately for Pullman’s employees, he ruled like an autocrat, prohibiting the publication of independent newspapers, town meetings, and open discussion. He was known to inspect the homes of workers for cleanliness, terminating leases on 10-days’ notice if conditions did not match his standards. Richard Ely, in an 1885 edition of Harper’s Weekly, wrote “The power of [Otto von] Bismarck in Germany is utterly insignificant when compared with the power of the ruling authority of the Pullman Palace Car Company…”

Ely later wrote, “It should be constantly borne in mind that all investments and outlays in Pullman are intended to yield financial returns satisfactory from a purely business point of view.” This was validated during the Panic of 1893 when Pullman cut wages in the face of decreasing demand for sleeper cars. His failure to adjust rent accordingly led to one of the largest strikes in the history of the United States.

Joining with the American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs, Pullman workers refused to work, blocked rail tracks, and threatened strike breakers. A spike in national attention led to an injunction ordering the strikers back to work, which Debs ignored. As a result, President Grover Cleveland dispatched 12,000 federal troops to end the strike leading to the deaths of 30 workers. Pullman’s reputation was tarnished as a result and his company town labeled “un-American.” Public opinion supported the use of federal troops to end the strike while the national media labeled strikers as foreigners and anarchists.

Pullman suffered a heart attack in 1897. His family was paranoid that railroad laborers would desecrate his body and went to extreme lengths to protect his final resting place. Placed in a lead-lined coffin, he was sealed in a block of concrete and then lowered into the ground. The grave was then covered with asphalt and tar paper, covered with a layer of concrete, surrounded by steel rails, and once again covered with concrete; the entire process took two days.