Vol. 6, No. 2 Although society laments the apparent death of objective journalism, bias in the media is far from a new phenomenon. In fact, the concept of nonpartisan news is just over a century old as journalism developed as a profession at the turn of the 20th century. Newspapers of the early 19th century provided political parties with official “organs” that disseminated platform-based editorials and spewed vitriol about rival candidates.

The history of newspapers in Orleans County is a lengthy one, but a story that originates in the early 1820s. Attributed as the first published newspaper in Orleans County, Batavia-native Seymour Tracy produced the short-lived Gazette in Gaines. Tracy, known locally as “One-Legged Tracy,” was recognized throughout Batavia for his intemperate habits leading fellow printers to attribute that behavior to the sudden failure of his paper. John Fisk, who worked with Tracy, picked up the loose ends and continued the newspaper as the Orleans Whig in 1827.

Other evidence suggests that Tracy published his first issue of The Gazette around 1824, which would make it the second paper published in Orleans County. The first, then, is attributed to Benjamin Franklin Cowdery who established the Newport Patriot in 1823. Born on May 26, 1790, at New Marlborough, Massachusetts, fellow printers regarded Cowdery as an “itinerant printer” due to his frequent movements across the wilderness of Western New York. His earliest newspaper publications included the Hamilton Recorder at Olean in 1819 and the Angelica Republican in 1820. According to published histories regarding the printing industry in Western New York, Cowdery was responsible for publishing at least eight different newspapers prior to 1830. This, in the mind of fellow printers, suggested that Cowdery was ill-equipped to speak on behalf of the profession.

Instead, Cowdery’s rapid establishment and sale of printing enterprises represents the volatility of newspaper publication on the frontier. As Cowdery learned in Olean, the number of paid subscribers was insufficient to support the ongoing operation of the paper. It is likely that he faced a similar realization in Albion leading to the sale of the Newport Patriot to Timothy Clapp Strong in February of 1825. The subsequent change of the paper’s name to The Orleans Advocate provided Strong with a fresh start for the newspaper in the burgeoning Canal town.

The disappearance of William Morgan in 1826 gave Strong, a long-standing Freemason, the opportunity to disavow the organization and rename his newspaper The Orleans Advocate & Anti-Masonic Telegraph in early 1828. The name was quickly shortened to The Orleans Anti-Masonic Telegraph in February of that year and by July 4, 1828, Strong’s name appears as a signer of the “Declaration of Independence” signed at the Convention of Seceding Masons held at LeRoy. The name change provides the first direct insight into the political leanings of the publication, but local pressure against the paper’s name must have been immense as Strong once again changed the name to The Orleans Telegraph in late 1828. The Republican leanings of the Telegraph led then Village of Albion president, Alexis Ward, to seek out Cephas McConnell to publish a Democratic-leaning paper.

The newspaper changed names to The American Standard and eventually became The Orleans American in 1833. Strong sold out to John Denio and moved to Geneva in order to attempt the establishment of another newspaper. In 1839, a newspaper article from the Wayne Sentinel highlighted Strong’s new venture. The article opened by referencing Strong’s unofficial title of “Iscariot, from whence obtained we do not know,” continuing, “We predict he will not meet with better success there, than in other places in which he has figured as a champion of anti-masonry…Timothy will find but few that will follow him as a political guide.” The nickname, derived from Judas Iscariot, is likely attributed to his betrayal of the Freemasons. By the mid-1830s, anti-masonry had melded into the Whig Party and the publication of such papers was viewed as obsolete.

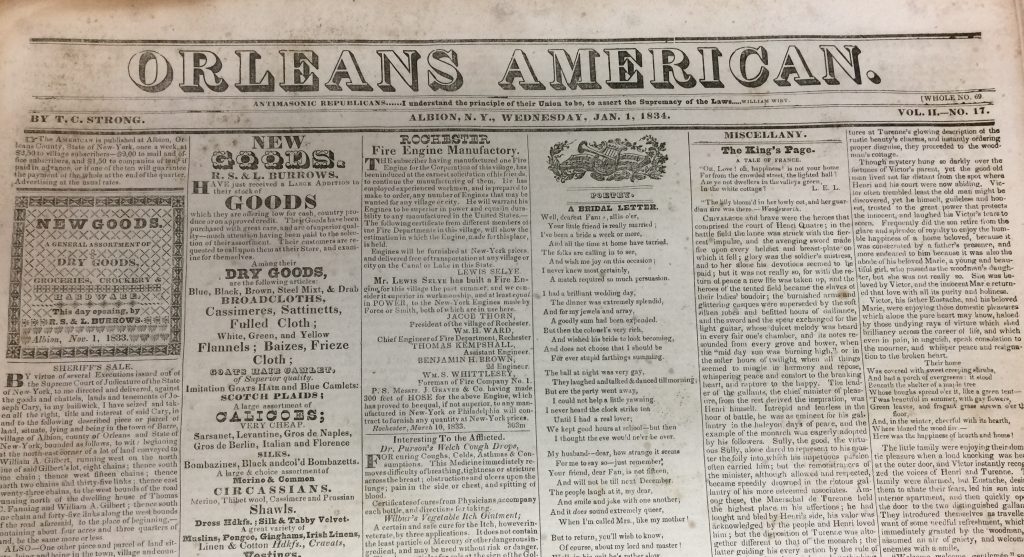

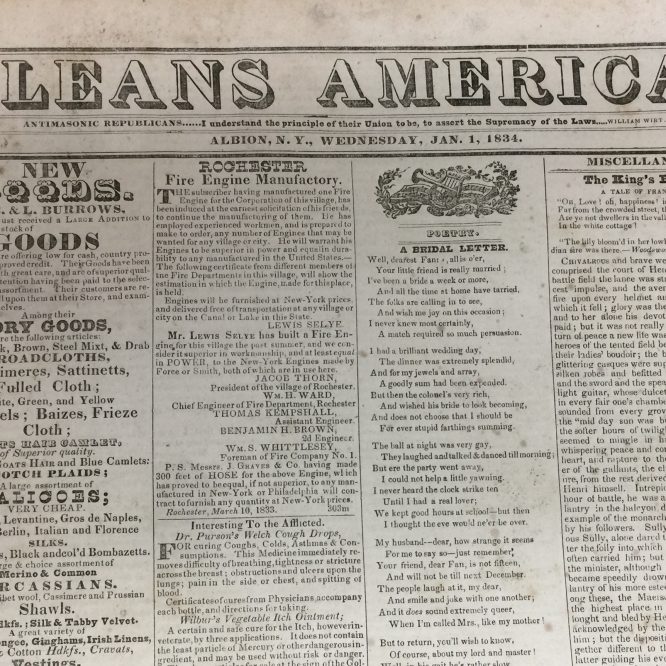

This masthead, from the Orleans American, reveals the limited amount of advertising matter in local papers during the early nineteenth century. The two largest advertisements relate to the dry goods business of Roswell and Lorenzo Burrows. Aside from legal announcements and advertisements, there are no articles concerning local matters in this early issue. The majority of the content consists of serialized literature, poetry, and state or national news. Printers often avoided publishing content that subscribers could get by word of mouth.