On the cusp of a series of large-scale collections projects, the idea of “weeding” surfaced yet again as one of the more controversial undertakings within libraries. It led me to think a little more intently about why we remove materials from our collections in a world where digital access seems unstable and often fleeting. When discussing the regular activities associated with the management of physical collections, no librarian will disagree with the rationale that library collections should be well-curated and accessible. Yet nothing elicits more fear than the act of taking away instead of adding.

The term “weeding” itself does a disservice to the act of judiciously vetting an existing collection. When I mow my lawn, I can easily spot the tufts of crabgrass that seem to consume the corners of my backyard and the occasional dandelion that pops up in my raised garden beds are easy to pluck from the soil. Weeding a collection can be, in some respects, just as simple. As in the case of paring down resources to reduce the collection’s physical footprint, sweeping decisions can be made by simply removing damaged books or pulling items that have never circulated. In other cases, we can pluck from the collection those ugly, invasive books with damaged spines, missing pages, dirt-covered, mold-invaded, or insect-infested. More time-consuming is the careful review and vetting of books based on content and currency.

Perhaps “deselection” or “culling” is better terminology. As defined by Merriam-Webster, culling (a population) is defined as “reduc[ing] in size by removal of especially weak or sick individuals.” So, can we have “sick” books? Sure, but not necessarily sick in the awesome sense. Those dirty, dusty, warped, and moldy books that were donated to the library by a well-intentioned patron might make me physically ill, but we might find that the content of a text is “sick” as well.

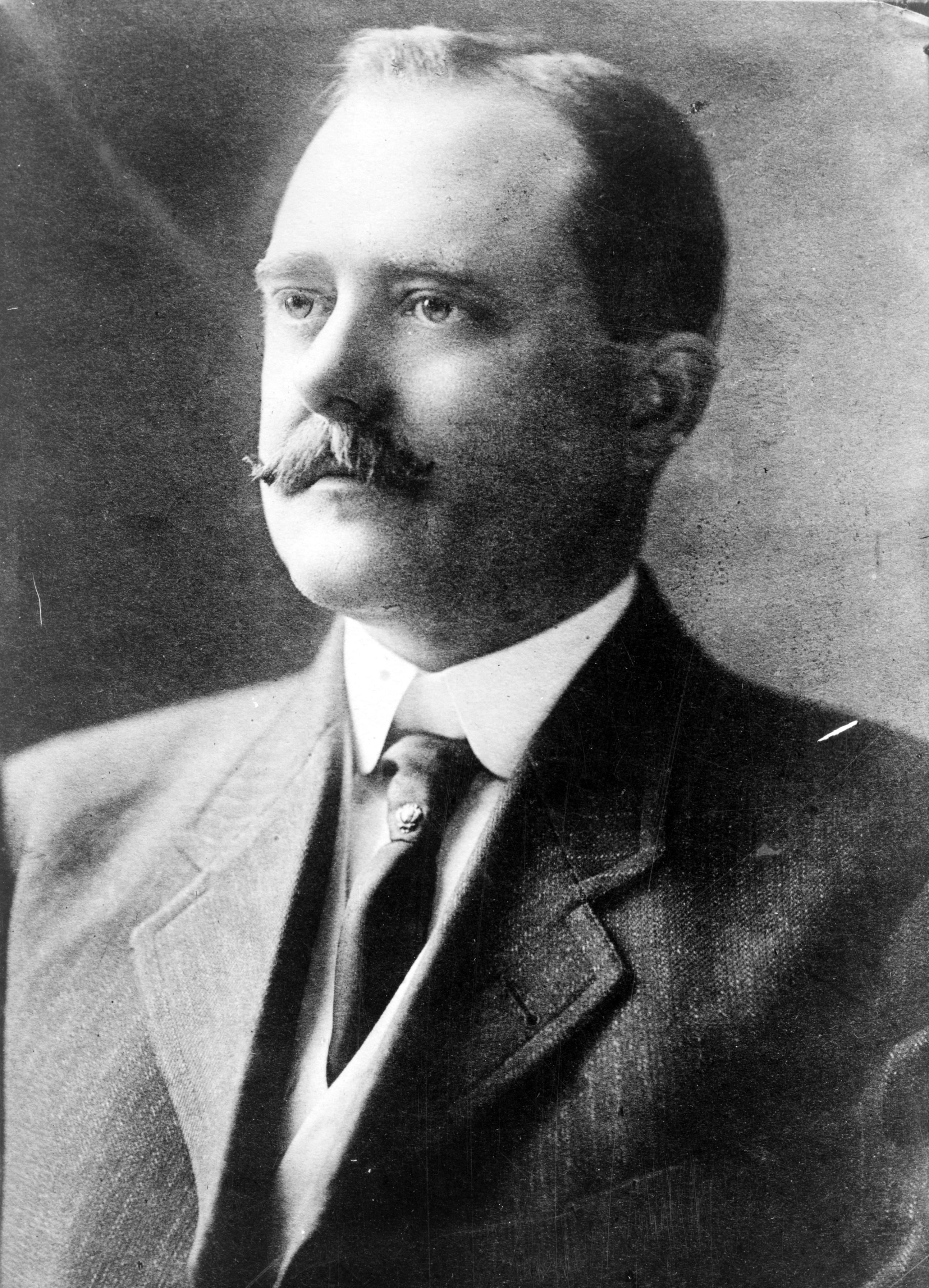

As I mentioned, the library is in the throes of preparation for upcoming collection development projects. Perusing the collection of titles, classified in the Dewey Decimal classification system, Clark Howell’s four-volume History of Georgia, published in 1926, stood out. Having spent some time in graduate school studying the American Civil War and Reconstruction and as a municipal historian in Western New York, I often grab older tomes relating to the history of Georgia to observe the coverage of Rufus Brown Bullock. The Albion, New York native became a polarizing figure in Southern politics amidst Reconstruction and, of course, Howell spared no expense in lambasting Bullock’s tenure as the state’s executive.

To be expected, Howell takes the typical “Lost Cause” approach to describing Reconstruction in the South, “…with the black problem knocking at the very hearthstones of every southern home, and with a great poverty-stricken section, bowed and prostrated by the reign of the carpetbag politicians…” (p.578). He takes particular care in attempting to distance the Southern cause from the actions of John Wilkes Booth, that Booth was disgruntled over a failed Presidential pardon, and that “…Lincoln and Booth were the best of friends, and had indeed been the same kind of cronies that thirty to forty years subsequently developed between President Grover Cleveland and his actor friend, Joseph Jefferson.”

It was the opening lines to Part IX that proved most startling, but not necessarily unexpected. As Georgia emerged from Reconstruction, Howell remarked that “Georgians felt like freemen again. Democracy was back into her own. White supremacy had conquered.” Typical of antebellum depictions of slavery in the South, he extensively quotes from Ulrich Bonnell Phillips’ Georgia and State Rights to describe the benevolence of slavers, who as Phillips claims, provided food, clothing, education, and healthcare for enslaved peoples.

Perhaps more startling is Howell’s thorough reference to Isaac Avery’s The History of the State of Georgia from 1850 to 1881 in which Avery attacked the “hidden partisan efficiency” of the Union League, which “ruled consummately its lettered legionnaires from Africa.” Howell makes sure to include a lengthy paragraph about the efforts of the Ku Klux Klan to combat the actions of the Union League. The quote calls out Avery’s own participation in the Klan, as he “knew all about it, and shared in its legitimate work.” Contrary to our understanding of the first KKK today, as a militant terrorist organization that ran rampant throughout the South during Reconstruction, Howell’s continued quotation of Avery’s work paints the Klan as “intended to aid the law and prevent crime…a matter of self-defense against plunder, assassination and rape,” a foundational point of the Lost Cause trope.

So this particular title was a stark indicator of the importance of carefully curated collections and a reminder of the need to conduct this work frequently. If we hope to establish libraries as a welcoming and inclusive environment, collections must stand as a reflection of the values that foster such an environment. And quite clearly, nothing could be further from inclusivity and welcoming than Howell’s nostalgic, white supremacist history of Georgia.